Happy Friday, and welcome to Food Fix! Thanks for being here. If you’re not yet a paid subscriber, you missed Tuesday’s rundown on a major retirement at FDA and key happenings in Washington this week. Subscribe now to get both weekly emails.

Food Fix in the news: In case you missed it, my story in Politico this week revealed FDA inspectors knew about the Cronobacter positive test – that ultimately led to a recent recall of infant formula – three months before the formula was recalled.

An editorial note: One question I’ve gotten recently: Why publish exclusive reporting in Politico and not here, in the newsletter? It’s a good question. The audience for Food Fix has grown substantially since I launched in August (my email list has nearly tripled), but for certain accountability stories with broad public interest, a news outlet like Politico or elsewhere is still going to reach far more people. The bigger platform made sense for this latest infant-formula recall story.

As always, I welcome your thoughts and feedback about this newsletter. Reply to this email or drop me a line: helena@foodfix.co.

Alright, let’s get to it –

Helena

***

Today, in Food Fix:

– Infant formula remains vulnerable to another crisis

– Vilsack pressed on making SNAP healthier

– SNAP work requirements debate gets testy

***

The national security risks we don’t think about

Nearly two decades ago, Health and Human Services Secretary Tommy Thompson shocked a news conference when he gave a particularly candid answer about the vulnerability of the U.S. food supply.

“For the life of me,” he said, “I cannot understand why the terrorists have not attacked our food supply because it is so easy to do.”

I found myself thinking about Thompson’s infamous quote after Tuesday’s House oversight subcommittee hearing on infant formula – not because I’m particularly worried about a terrorist attack on food, or, god forbid, formula, but because it’s a reminder that when public officials are this candid about such risks, it’s usually worth paying attention. (By the way, after 9/11, Congress gave sweeping new powers to the FDA to help the agency be more prepared for potential attacks, including some basic things like ensuring the agency knows where food plants are located.)

During this week’s hearing, Frank Yiannas, FDA’s former deputy commissioner for food policy and response, was pretty clear in warning Congress that the infant formula crisis could happen again.

“The nation remains one outbreak, one tornado, flood or cyber attack away from finding itself in a similar place to that of February 17, 2022,” Yiannas told the committee, referring to the date of the massive Abbott Nutrition formula recall.

Yiannas also said he believed the crisis could have been “averted,” or at least “the magnitude lessened” if the agency had acted more quickly, though I’m not going to relitigate the FDA’s many missteps here. (Go here, here, and here for that.) In his full testimony Yiannas laid out several policy recommendations.

To be clear, this was not a hyperbolic warning from some rando – Yiannas was just on the inside at FDA. And the notion that this type of crisis could happen again is essentially the current consensus view in Washington. (Yiannas’ warning is also what was picked up in the press, including the Wall Street Journal, CNBC, and Axios, to name a few.)

As I reported last month, FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner Janet Woodcock was similarly candid on a recent call with reporters.

“We’ll do everything we can. But this could happen again,” Woodcock said, specifically referring not to food safety concerns but to how consolidated infant formula production remains (something that is outside of FDA’s jurisdiction). “When you only have a few manufacturers, you’re going to be vulnerable,” she added.

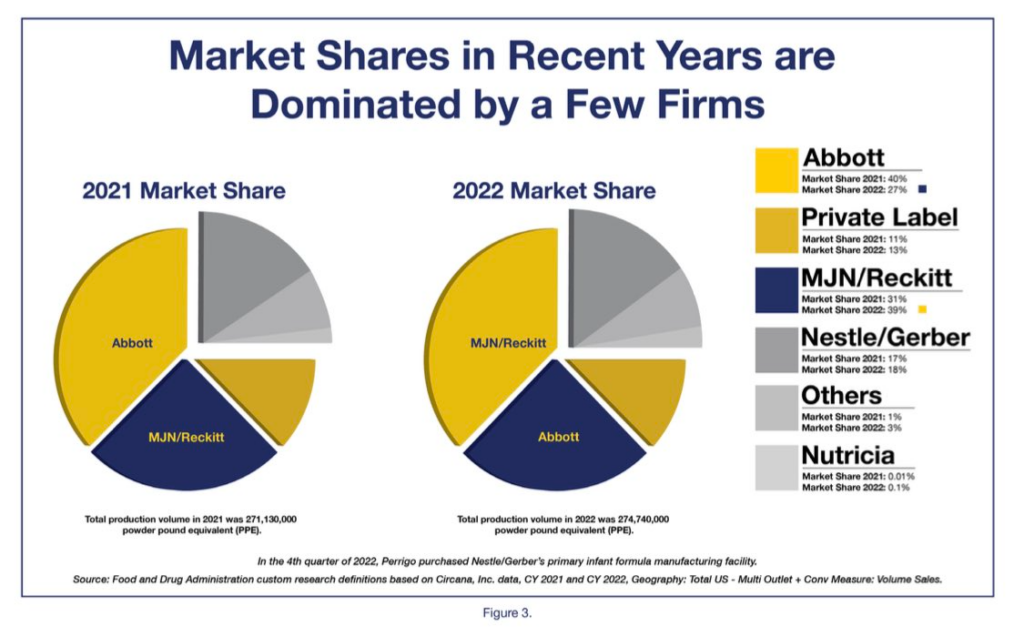

The infant formula market is no less consolidated today than it was in 2021, as illustrated in a new report on infant formula resiliency FDA released on Tuesday ahead of the hearing. This chart, which shows that Reckitt-Mead Johnson basically just traded places with Abbott, in terms of market share, stood out to me:

Formula is different: Throughout the pandemic we saw all types of short-term food shortages and disruptions. Most foods, however, we can live without, at least temporarily – you can try a different kind of pasta or eat something else. Infant formula is not one of those foods. It has no replacement. (Human milk is, of course, very important, but lactation can’t be restarted easily, and health or logistical issues make formula the only or preferred option for many.)

Certain metabolic and specialty formulas are also essential – and not just for infants, but children and adults, too. Thousands of people literally cannot live without these products. During the worst periods of this shortage, some individuals were hospitalized due to a lack of formula.

It could have been much worse.

Beyond FDA: FDA has an important role here, for sure, but as it was made clear at the hearing this week, it would take a much broader effort by the federal government to make the infant formula sector more resilient. FDA has oversight of nutrition and food safety requirements, and increasingly, supply chain monitoring – but the agency doesn’t enforce antitrust laws or oversee the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), a USDA program through which more than half of U.S. formula is purchased.

In addition to the whole “this could most certainly happen again” takeaway, there were a handful of other notable themes that emerged from the hearing:

More oversight is coming: This subcommittee seems serious – and surprisingly bipartisan. A lot of people I talked to ahead of the hearing were worried that House oversight – known for being among the most partisan of theaters on Capitol Hill – would devolve into party-line bickering. It didn’t. One source I talked to this week called the hearing “a breath of fresh air” because it was surprisingly substantive and bipartisan.

Both leaders of the panel – Rep. Lisa McClain (R-Mich.), chair, and Rep. Katie Porter (D-Calif.), ranking member – said they were not only working together, but eager to hold more hearings to push for reforms. Democrats on the panel were somewhat less hard on FDA, but they didn’t give the agency a pass, either.

“Nobody gets a pass today,” Porter said. “Yes, the FDA must do better, it could have been faster and more adept at anticipating the formula crisis … so there’s no pass for the FDA here, but lawmakers also have to do better by providing the FDA with the resources and the authorities they need.” Porter also called out Abbott for “engaging in negligent behavior.”

(Abbott, for its part, maintains that its products did not cause the reported infant illnesses and deaths that prompted a for-cause inspection and then a months-long plant shutdown over insanitary conditions. “At Abbott, the quality and safety of our products is always a priority—and it’s important to remember that no sealed, distributed product from our Sturgis, Mich., facility tested positive for the presence of Cronobacter,” a spokesperson said this week.)

FDA next? McClain told me she’s pressing for current FDA officials to appear and answer questions before the committee. “They’re trying to avert and prolong and delay and deflect,” McClain said in an interview. “The longer we deflect and delay, the more infants are going to get sick and potentially die. What’s the delay?”

I asked McClain how many hearings she planned to hold and she replied: “As many as it takes to make some change and reform.” McClain said she’d asked for the FDA to appear April 19, but that has not been confirmed.

The agency has been asked to turn over a large volume of documents and communications regarding the infant formula response to the subcommittee.

FDA’s view: The FDA maintains the agency has not delayed any of its work on infant formula, including both improving safety oversight and trying to make the industry more resilient to future shocks, though much of that is beyond the agency’s purview. FDA worked with Congress last year to get language in the omnibus spending bill to require “critical foods” manufacturers to have redundancy plans in place.

The agency is also creating a new Office of Critical Foods to oversee infant formula and other essential medical foods. (P.S. If you want to help lead this office, FDA has posted several job openings here.)

FDA needs clear reporting authority: Another common theme throughout the hearing, raised by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and several others, was broad agreement that FDA should be given authority to mandate that formula makers proactively disclose to FDA when they find Cronobacter or Salmonella in their products, even if those products haven’t shipped out.

FDA recently asked Congress for this authority in the administration’s budget request. Some consumer advocates, however, believe FDA already has this authority. (Scroll to the bottom of this story for more on this legal debate.)

FDA contends this requirement would help the agency identify problems in plants early and hopefully also reduce the number of formula recalls. We’ve had four Cronobacter-related recalls in the past year or so – more than the past decade combined. (See here for a helpful timeline.)

WIC needs to be looked at: During the hearing, several Democrats and Republicans raised the need to look at the role of WIC, since it’s used for the majority of U.S. formula purchases. The extent to which sole-source state contracts, primarily with Abbott and Reckitt-Mead Johnson, may have fueled market consolidation is of great interest.

The National WIC Association (NWA), which represents agencies that implement WIC, issued a statement in response to the hearing cautioning against any “hasty reforms” that could raise program costs.

“Let’s be clear: WIC did not cause the infant formula shortages,” said Jamila Taylor, president and CEO of NWA. Taylor added: “It is important to recognize the complex factors that led Congress to require sole-supplier contracts in the first place. WIC families deserve choice, but Congress cannot create an unlimited subsidy for infant formula manufacturers. Policymakers must strike a balance between containing costs and ensuring sufficient funding to serve WIC’s caseload.”

There are not any serious conversations on the Hill about actually reforming WIC contracts – that I’m aware of anyway – but it was interesting to hear lawmakers raise the concern.

Another slow recall: In case you missed it, my Politico story on FDA’s slow timeline for a recent infant formula recall also came up on the Hill multiple times this week, as lawmakers questioned FDA Commissioner Robert Califf in a separate hearing about the agency’s operations and fiscal 2024 budget request.

TL;DR: FDA inspectors first became aware in November 2022 of the positive Cronobacter test that ultimately sparked the recall of 145,000 cans of Enfamil ProSobee Simply Plant-Based Infant Formula, but the recall didn’t come until late February 2023. The recall was announced five months after the products were distributed nationally in early September.

There’s a lot to unpack here. I encourage you to read the full story, which includes FDA’s responses to my questions about the timeline.

***

Vilsack pressed on making SNAP healthier

Rep. Andy Harris (R-Md.), chairman of the House Appropriations subcommittee that funds food and agriculture programs, on Thursday pressed Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack on trying to leverage the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (AKA food stamps) to encourage healthier food purchases.

Harris asked Vilsack if he could share the exact percentage of SNAP dollars that go toward purchasing sugar-sweetened beverages. Vilsack said he didn’t have the figure, but pushed back on the premise that perhaps there should be restrictions on what types of foods SNAP could be used for.

“There are many challenges with that notion,” Vilsack said. “I think it’s important to understand what we’re not trying to do is to stigmatize people that are struggling financially.”

Vilsack also said purchase restrictions were technically challenging and could broadly increase stigma for the program.

Harris pushed back on that: “This is a huge area of opportunity to improve the nutrition of Americans and to do it through the SNAP program,” he said.

Context: The idea of purchase restrictions for SNAP is something that comes up periodically, and will probably come up more this farm bill cycle, but there is no political path forward to doing this, or even to allow a state to test the idea. In the past, states seeking waivers to test such restrictions have been denied by USDA.

***

SNAP work requirements debate gets testy

There were so many hearings on Capitol Hill this week that I skipped Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack appearing before the House Agriculture Committee, but apparently the hearing was dominated by partisan sniping over a recent Republican push to impose stricter work requirements on SNAP.

Jerry Hagstrom of The Hagstrom Report had a good recap of the hearing: “The conflict began when Rep. David Scott (D-Ga.), in his opening statement, said he was ‘disturbed’ by Republican farm bill proposals that would impose stricter work requirements on the SNAP beneficiaries known as Able-Bodied Adults Without Dependents.”

“More requirements will only leave vulnerable populations – like veterans – hungry,” Scott said, per Hagstrom’s report. “SNAP already has strict work requirements, and it is a very effective work support program. The House Democrats will stand united to defeat any proposals to weaken SNAP, as we have in previous farm bill years.”

Rep. Dusty Johnson (R-S.D.) pushed back and “called Scott’s comments ‘unfortunate’ and pointed out that work requirements were put in place in 1996 when Congress passed a farm bill and a welfare reform bill, both signed by then-President Bill Clinton, a Democrat,” Hagstrom added.

Johnson posted his heated response during the hearing on YouTube. Brush up on the broader politics of this SNAP fight here.

***

What I’m reading

LGBTQ food-stamp lawsuit by GOP states dismissed (Bloomberg). “A Biden administration rule barring states from discriminating against poor LGBTQ people in the distribution of food stamps and other nutrition assistance programs survived a legal challenge by almost two dozen Republican-led states,” reports Erik Larson. “The lawsuit filed in July exaggerated the impact that the federal regulation would have on religious freedom, and improperly tied the new rule to unrelated issues around transgender rights, US District Judge Travis R. McDonough said in the decision Wednesday in Knoxville, Tennessee.”

Scientists create woolly mammoth meatball– but are too scared to eat it (New York Post). “Ever wonder what prehistoric creatures tasted like? We could soon find out: An Australian food firm has devised a prime-eval meatball from the resurrected flesh of – wait for it – the long extinct woolly mammoth,” reports Ben Cost. The product was made by “Vow, an Australian company that cultivates cells from the biopsies of unconventional animals to create better more sustainable types of meat.”

Italy wants to ban lab-grown meat to protect culinary heritage (Bloomberg). “Italy’s government introduced a draft law that, if approved, will ban the production and sale of cultivated food and meat,” Alessandro Speciale reports. “We are proud to be the first nation in the world to stop this decadence,” said Augusta Montaruli, a lawmaker from Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party.

***

Unlock more from Food Fix

Here’s a nice endorsement we got from a paid subscriber: “Our team has been loving the premium content on Tuesdays since we signed up – many of us are wondering how we lived with only the Friday newsletter for so long.” (But seriously, how?)

Subscribe to Food Fix to unlock access to not one, but two newsletters each week, packed with insights and analysis on food happenings in Washington and beyond.

You can also follow Food Fix on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Get on the list: If someone forwarded you this newsletter, sign yourself up for the free Friday edition.

See you next week!