Happy Friday, and welcome to Food Fix. Glad to be back in everyone’s inboxes after spring break with my kiddos last week, even though there was a whole bunch of news I missed (here’s a quick recap, icymi.)

Upgrade to get more: Friendly reminder that upgrading to get Food Fix twice a week is the best way to make sure you don’t miss a thing.

As always, I truly appreciate your feedback. Reply to this email to land in my inbox, or drop me a note: helena@foodfix.co.

Alright, let’s get to it –

Helena

***

The RFK Jr. food dye crackdown marks a totally new era in food policy

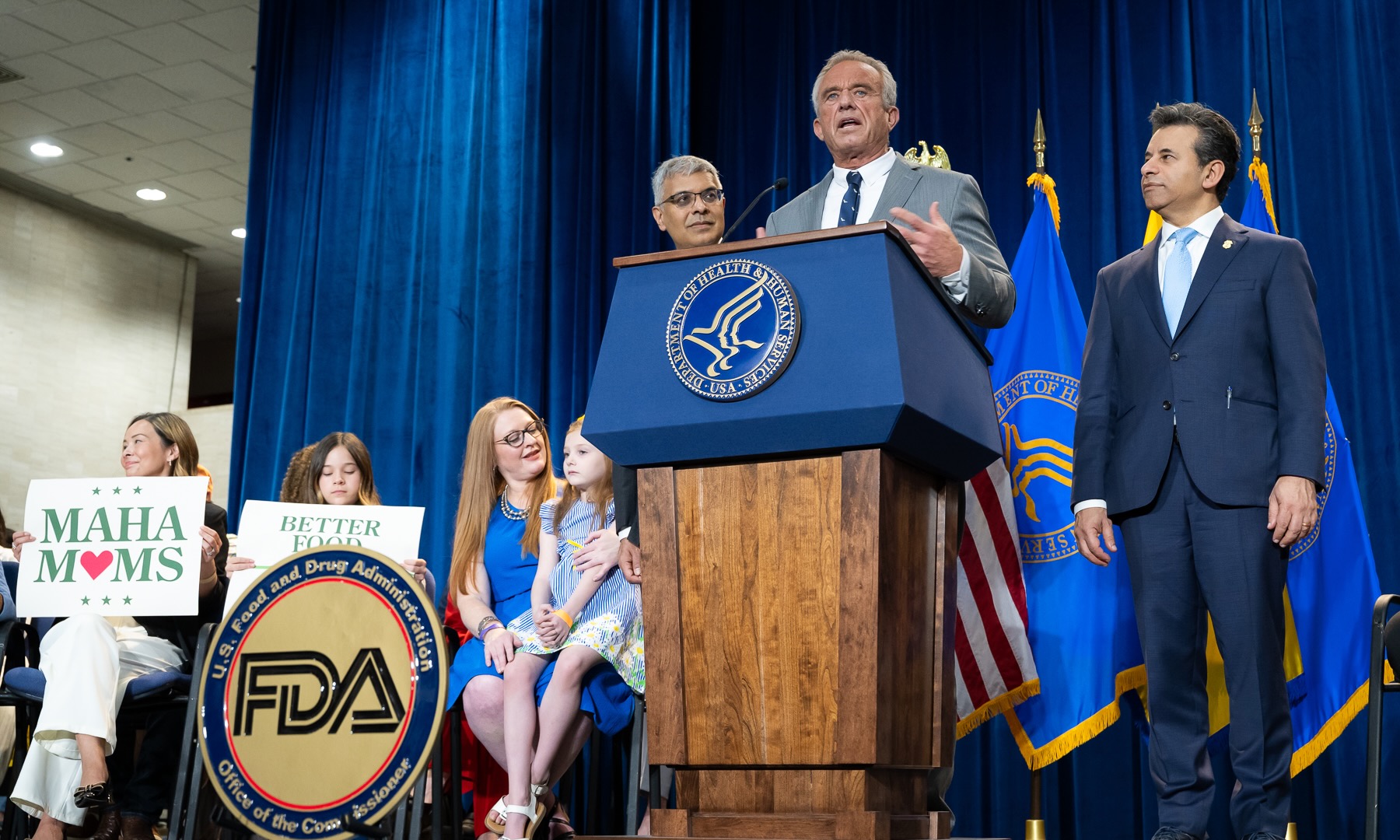

The Trump administration’s declaration that it would get synthetic food dyes out of the U.S. food supply by the end of next year made a lot of waves this week.

Several news outlets reported (incorrectly) that the dyes were all being banned (nothing has been banned yet). Still, plenty of people cheered the move as a win for consumers and kids, while some critics derided it as, at best, pointless and, at worst, not science-based.

But if you take a step back from all the noise, what this really marks is a completely new era for food policy.

FDA is unrecognizable: In a matter of weeks, the FDA has gone from an agency that was known for being extremely careful and cautious — sometimes taking decades to decide or act as science was reviewed — to one that is plowing full steam ahead without going through any of the typical processes, like performing a risk assessment or posting a regulatory notice for comment. All policy dynamics and norms have been turned upside down. Top health officials are now calling ingredients “poison” that the agency had not only approved but for decades stood behind their safety assessments. The food dyes announcement itself was kept under tight wraps: Consumer groups and food industry leaders were not briefed, as is typical for a big policy change like this. Most staff who work on food additives within the FDA were not even briefed, let alone consulted.

What happened: The agency announced Tuesday that it was “establishing a national standard and timeline for the food industry to transition from petrochemical-based dyes to natural alternatives.” This was broadly misunderstood to mean food dyes had been banned, but that’s not what happened. To ban synthetic food dyes, FDA would need to go through a regulatory process and make a scientific case for why they should be banned. The agency has not done that, at least not yet.

FDA did say this week that it is “initiating the process to revoke authorization” for two synthetic food dyes: Citrus Red No. 2 and Orange B within the “coming months.” These are really minor ingredients — my understanding is that Citrus Red is sometimes used on outside of some orange peels (primarily from Florida), and Orange B was once used in the casings of some sausages and hot dogs, but hasn’t been used by industry for decades. (FDA actually proposed banning Orange B back in 1978, but never finalized the ban, perhaps because the industry was abandoning it anyway.)

The big fish here are Green No. 3, Red No. 40, Yellow No. 5, Yellow No. 6, Blue No. 1 and Blue No. 2 — six dyes that are used widely across hundreds of thousands of products, from cereals and drinks to chips and candy. For these, FDA merely said it was “working with industry” to eliminate them from the food supply by the end of next year, which would be a quick turnaround for such a change.

No deal: During a press conference Tuesday, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. suggested that the food industry had agreed to this timeline, ostensibly because food companies were desperate to avoid a patchwork of state laws. But the industry has not actually agreed to do this, and certainly not by the end of next year.

During the presser, I was able to ask Kennedy what the plan is if the industry doesn’t agree to pull these dyes voluntarily — since, again, nothing has actually been banned.

“Here the industry has voluntarily agreed,” Kennedy replied. I found this baffling, because I knew the industry had not.

Later on, Sheryl Gay Stolberg of the New York Times pressed again on this question of what had actually been agreed to, and Kennedy softened his answer: “We don’t have an agreement.” he said. “We have an understanding.”

Bloomberg on Wednesday pinned this down even further: None of the major industry groups or companies has struck an agreement on voluntarily phasing out food dyes. One exception: Dairy processors did narrowly commit this week to pull synthetic dyes from products destined for schools.

Consumer groups are generally furious with the Trump administration for cutting public health agencies, pulling back environmental regulations, disbanding key food safety committees and so on. Just this week, USDA pulled the plug on an effort to reduce salmonella contamination in poultry, but the consumer lobby also generally supports getting rid of synthetic dyes because some studies have linked them to behavioral problems in children and other health concerns.

Center for Science in the Public Interest president and executive director, Peter Lurie, said this week: “We wish Kennedy and Makary well getting these unnecessary and harmful dyes out of the food supply and hope they succeed. … But history tells us that relying on voluntary food industry compliance has all-too-often proven to be a fool’s errand.”

There isn’t some grand compromise across the industry to voluntarily pull bright colors from the market in the next 18 months. But it’s also true that the food industry is completely backed into a corner on synthetic dyes and will almost certainly have to remove them in the coming years. West Virginia’s ban on food dyes takes effect in 2028, and some states have banned the ingredients from school food more quickly than that. These looming state bans — and many more bills in the works — give the feds a lot of leverage here.

And the FDA hasn’t ruled out taking regulatory action. “You win more bees with honey than fire,” Makary told reporters Tuesday. “There are a number of tools at our disposal. I believe in love, and let’s start in a friendly way and see if we can do this without any statutory or regulatory changes. But we are exploring every tool in the toolbox to make sure this gets done very quickly.”

Poison squad: It’s not just process and norms that have radically changed in recent weeks — but also language. We are in new territory as top FDA and HHS officials use terms like “poisonous” and “toxic” to describe ingredients that have previously been either approved or considered safe by FDA. (While top officials publicly blame food dyes for behavioral problems in children and even cancer, FDA’s website still defends the safety of the products: “The totality of scientific evidence shows that most children have no adverse effects when consuming foods containing color additives, but some evidence suggests that certain children may be sensitive to them.”)

We are in a new world where many of FDA’s norms have been shredded. And food dyes are likely just the beginning. Kennedy on Tuesday also bluntly declared: “Sugar is poison. And Americans need to know that. It is poisoning us. It’s giving us a diabetes crisis.”

I truly never thought I’d ever hear a cabinet official say something like this. In the past, FDA has clearly defended the American food supply as safe, even as officials started to raise some concerns about ultra-processed foods in the past year or so. Now the official line from FDA and HHS is that much of our food supply is poisoning us.

(By the way, I couldn’t help but notice the very same day RFK Jr. called sugar poison, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins was visiting a sugar plant in Minnesota. I can only imagine the phone calls she’s likely getting from the sugar industry over this.)

Courtney Gaine, president and CEO of the Sugar Association, said in a statement that the “demonization of real sugar — grown by American sugarbeet and sugarcane farmers — is counterproductive.” She noted that added sugars consumption in the U.S. is “at its lowest in 40 years, while obesity continues its relentless rise.”

Kennedy, for his part, said on Wednesday that industry pushback isn’t slowing him down one bit.

“We are going to have revolutionary change,” Kennedy said. “If you think that we’re not serious about this, you’re making a bad judgement. I have a president now behind me who does not care. He doesn’t care. He’s been called by every soda company, every candy company, every processed food company, and most of the time he tells me and says I don’t care.”

***

What I’m reading

North Dakota’s pesticide protection law a first for the US (North Dakota Monitor). “North Dakota is poised to be the first state in the nation to implement a law that provides legal protections for pesticide manufacturers — an issue that has been debated in legislatures across the country in the face of large payouts to cancer victims,” reports Jeff Beach. “Gov. Kelly Armstrong on Wednesday signed House Bill 1318 that specifies that a label approved by the Environmental Protection Agency acts as sufficient warning to users about the hazards posed by pesticides and herbicides such as Roundup. Georgia’s General Assembly passed its version of the pesticide protection bill but it has yet to be signed. Ag groups have lined up behind the pesticide legislation, saying it ensures farmers will have access to chemicals they need to control weeds and insects. Critics have said the bill will make it harder for people harmed by chemicals to win lawsuits against the manufacturers of chemicals.”

USDA withdraws a plan to limit salmonella levels in raw poultry (Associated Press). “The Agriculture Department will not require poultry companies to limit salmonella bacteria in their products, halting a Biden Administration effort to prevent food poisoning from contaminated meat,” Jonel Aleccia reports. “The department on Thursday said it was withdrawing a rule proposed in August after three years of development. The rule would have required poultry companies to keep levels of salmonella bacteria under a certain threshold and test for the presence of six strains most associated with illness, including three found in turkey and three in chicken. If the levels exceeded the standard or any of those strains were found, the poultry couldn’t be sold and would be subject to recall, the proposal had said. The withdrawal drew praise from the National Chicken Council, an industry trade group, which said the proposed rule was legally unsound, misinterpreted science, would have increased costs and create more food waste, all ‘with no meaningful impact on public health.’ But the move drew swift criticism from food safety advocates, including Sandra Eskin, a former USDA official who helped draft the plan. The withdrawal ‘sends the clear message that the Make America Healthy Again initiative does not care about the thousands of people who get sick from preventable foodborne salmonella infections linked to poultry,’ Eskin said.”

Chobani announces $1.2 billion factory project for Oneida County; New York on track for dairy boom (The Daily News). “New York will soon be home to the single largest natural food processing facility in the country — Chobani,” writes Alex Gault. “The upstate-based yogurt and dairy foods company, announced with much fanfare on Tuesday that they are moving forward with a $1.2 billion project in Rome, Oneida County to create a 1.4 million-square-foot manufacturing center in the city’s Griffiss Business and Technology Park. New York State has already spent $23 million to spur the project along, investing last year in infrastructure and transportation improvements at the park. Empire State Development will provide another $73 million in tax credits if Chobani hits its job creation goals. That means a huge spike in milk demand — officials said the plant will process more than 12 million pound of milk a day, sourced from nearby dairy farms, including many in the north country. Chobani sources its milk from the Dairy Farmers of America milk cooperative, one of the larger co-ops in the northeast with over 350 member-farms in New York alone. Jay Matteson, Jefferson County’s agricultural coordinator, said he expects the Chobani project will increase demand for farms all across New York, DFA members and those in other co-ops, because the Chobani factory will require so much milk that the DFA farms will likely sell less to other sources. It’ll dovetail with at least six other major dairy industry projects under development right now, he said, part of a push that’s quickly boosting New York’s dairy industry.”

Trump cuts threaten agency running Meals on Wheels (New York Times). “Every Monday, Maurine Gentis, a retired teacher, waits for a delivery from Meals on Wheels South Texas,” writes Reed Abelson. “Living alone and in a wheelchair, she appreciates having someone look in on her regularly. The same group, a nonprofit, delivers books from the library and dry food for her cat. But Ms. Gentis is anxious about what lies ahead. The small government agency responsible for overseeing programs like Meals on Wheels is being dismantled as part of the Trump administration’s overhaul of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Roughly half its staff has been let go in recent layoffs and all of its 10 regional offices are closed, according to several employees who lost their jobs. In President Trump’s quest to end what he termed ‘illegal and immoral discrimination programs,’ one of his executive orders promoted cracking down on federal efforts to improve accessibility and representation for those with disabilities, with agencies flagging words like ‘accessible’ and ‘disability’ as potentially problematic. Certain research studies are no longer being funded, and many government health employees specializing in disability issues have been fired. The downsizing of the agency, the Administration for Community Living, is part of far-reaching cuts planned at the H.H.S. under the Trump administration’s proposed budget. While some federal funding may continue through September, the end of the government’s fiscal year, and some workers have been called back temporarily, there is significant uncertainty about the future.”

***

Why you should upgrade to a paid subscription to Food Fix

Become a paid subscriber to unlock access to two newsletters each week, packed with insight, analysis and exclusive reporting on what’s happening in food, in Washington and beyond. You’ll also get full access to the Food Fix archive — a great way to get smart on all things food policy.

Expense it: Most paid subscribers expense their subscriptions through work. It’s worth asking!

Discounts: We also offer discounts for government, academia and students. See our subscription options. Individuals who participate in SNAP or other federal nutrition programs qualify for a free Food Fix subscription — just email info@foodfix.co.

Get the Friday newsletter: If someone forwarded you this email, sign yourself up for the free Friday edition of Food Fix. You can also follow Food Fix on X, Bluesky and LinkedIn.

See you next week!