Happy Friday and welcome to Food Fix. Are you a paid subscriber yet? If not, you are missing out on the Tuesday newsletter. This week, I looked at whether school food got worse due to the pandemic, why a key House Oversight Committee may haul FDA to the Hill, and I correctly predicted the Dietary Guidelines were about to kick into gear (more on that below).

Unlock access to Tuesday editions by becoming a paid subscriber here.

FDA reporting in the news: The St. Louis Post-Dispatch editorial board recently reprinted the Washington Post editorial calling for the FDA to be broken up, noting that the editorial board agreed. The piece cites my reporting on the agency. A new opinion piece by Dave Dickey over at Investigate Midwest also backed the idea.

As always, I want to hear from you. Question for today: How did you find this newsletter? Reply to this email or shoot me a note: helena@foodfix.co.

Alright, let’s get to it –

Helena

***

Today, in Food Fix:

– We didn’t get a new food pyramid—so why is everyone acting like we did?

– Wide range of experts named to the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee

***

How the new ‘food pyramid’ went viral

Like millions of others, you may have recently seen social media posts or TV segments falsely claiming that a new government-backed food pyramid recommends Lucky Charms as healthier than steak.

The claim has gone viral on multiple social media platforms, been the subject of numerous Fox News segments, and was just shared by Joe Rogan, host of one of the most popular podcasts in the country with a huge following. This blew up so much that Snopes even did a fact check on it.

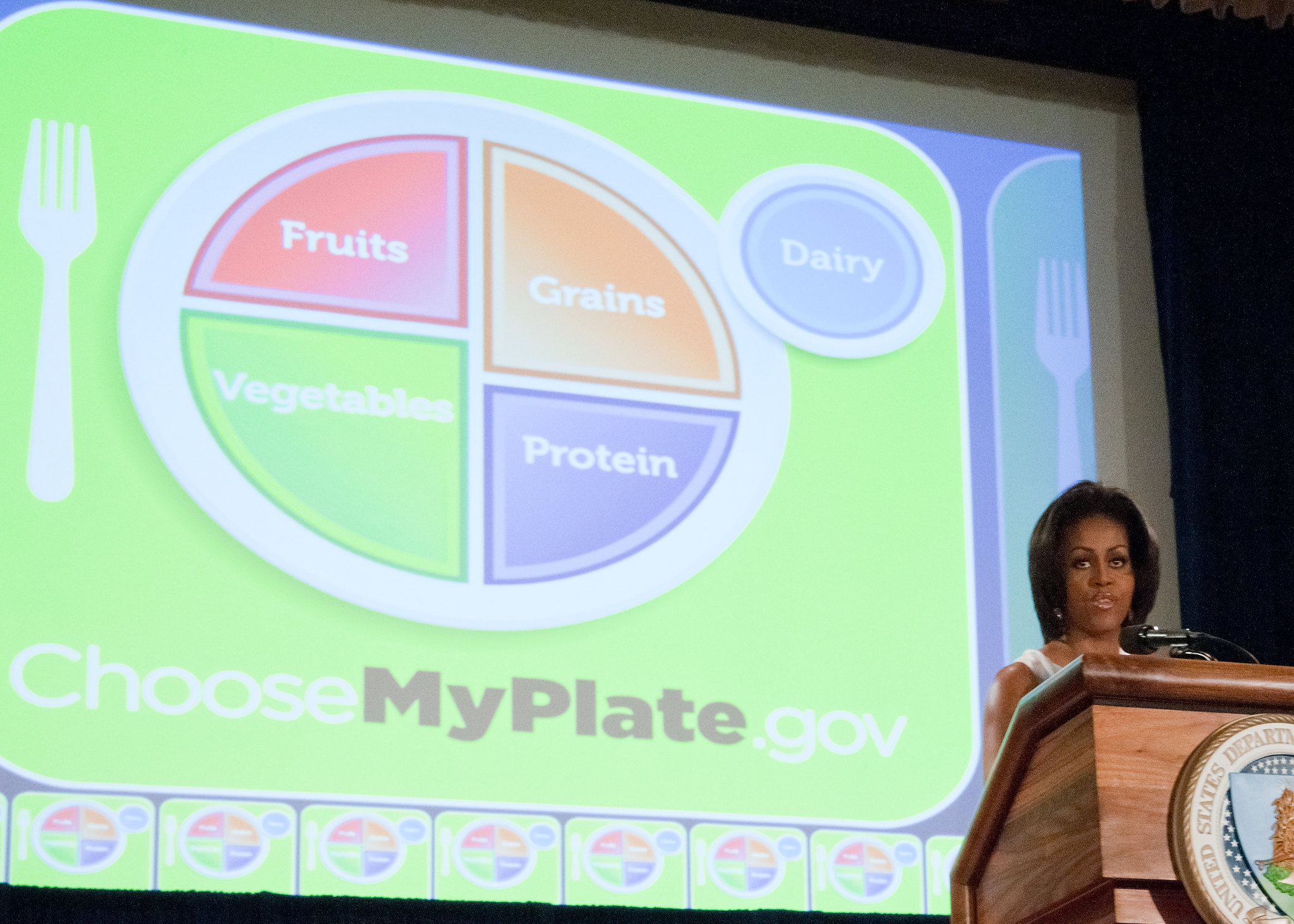

For the record, we do not have a new food pyramid. Many people don’t realize the food pyramid was actually retired more than a decade ago, when the Obama administration updated federal nutrition messaging to a plate visualization, AKA MyPlate. (Most people have also never heard of MyPlate, as I noted recently.)

So why does the internet think we have a new food pyramid?

To understand, we have to rewind more than a year. In October 2021, nutrition researchers at Tufts University published a paper in the journal Nature Food debuting the findings of a new food-nutrient profiling system they’d developed called Food Compass.

“While broad outlines of a healthful diet are clear—for example, eat more fruits and vegetables, and avoid soda—ambiguity exists on how to distinguish many other food groups, packaged and processed foods, and restaurant and mixed-food dishes, which together represent the majority of most diets,” read the paper, led by then-dean of the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, Dariush Mozaffarian.

“Clear metrics to characterize the healthfulness of these food items as well as groups of items, such as whole meals, diets or company product portfolios, are essential,” the paper’s authors wrote.

Food ranking 101: Nutrient profiling systems, which rank or rate foods based on health criteria, have been around for decades, but they’ve recently gained more traction as governments look to tackle diet-related diseases. The overall goal is to make it easier for consumers to identify healthier options, but developing these systems gets complicated – and controversial – quickly.

Existing nutrient profiling systems (such as Nutri-Score in Europe or Guiding Stars, which is used by grocery stores like Giant and Food Lion) are not holistic enough, the researchers argued in the paper, because they narrowly focus on nutrients and don’t account for things like the level of food processing or other attributes like phytonutrients or probiotics.

In contrast, the Tufts Food Compass was billed as more comprehensive. Here’s a visual sampling of the findings that Tufts shared at the time. Foods listed in green are encouraged, foods in blue are recommended in moderation and foods in red should be minimized, per the system.

The paper itself garnered a fair amount of press attention, including from the Daily Mail: “Why Cheerios are better than coffee for breakfast, according to scientists in a new study that will make you question everything you eat.”

The story of a chart: Soon after the research was published, global nutrition scientist Ty Beal took issue with numerous Food Compass ratings. Beal compiled some of the findings he found puzzling in a chart, which he posted on Twitter:

“Lucky charms, cheerios, sweet potato fries, grape juice & watermelon all score at least twice as high as eggs, cheese & beef in a new healthfulness metric,” Beal wrote. “Do we really want this for front-of-package [labeling], warning labels, taxation and company ratings?”

The post inspired some outrage on Twitter, but it didn’t go fully viral. At the time, Beal also responded to people who were expressing animosity toward the Tufts researchers: “I am confident they all care deeply about improving people’s health and nutrition,” he wrote. “I just think there are some blind spots and the system has flaws.”

The debate briefly quieted down, until … Six months later, in July, Nina Teicholz, an author, low-carb advocate and vocal critic of federal nutrition advice, published a newsletter titled “Cheerios a Health Food, Says Leader of White House Conference on Nutrition.” (Note: Mozaffarian did advocate for a White House conference on hunger, nutrition and health, which was held in September, but he did not lead it; he co-chaired a separate outside taskforce.)

“What kind of dystopian world has nutrition ‘science’ entered into whereby a university, a peer-reviewed journal, and one of the field’s most influential leaders legitimize advice telling the public to eat more Lucky Charms and fewer eggs?” Teicholz wrote.

The chart that Teicholz included in her newsletter came from an early version of a paper by Beal and many other scientists that critiqued the Food Compass. (More on the critiquing paper in a bit.) This chart (shown below) included more ratings examples than the original chart Beal posted on Twitter.

Teicholz’ newsletter caught the attention of Justin Mares, founder of bone broth company Kettle & Fire and co-founder of TrueMed. (You may recall I recently mentioned Mares and TrueMed in a similar firestorm over Coca-Cola.)

In November, Mares wrote a guest post criticizing the Food Compass for Pirate Wires, a popular newsletter run by Mike Solana, vice president of Founders Fund, a leading venture capital firm in Silicon Valley co-founded by Peter Thiel, one of the biggest donors in Republican politics. The piece, “NIH-Funded ‘Food Pyramid’ Rates Lucky Charms Healthier Than Steak,” came together, Solana said, after he and Mares spoke at a gathering hosted by Founders Fund. “Over dinner, our conversation turned to diet, and to my delighted horror I learned the tale of Tufts’ insane new food recommendations,” he wrote. “Immediately, I knew I had to share it with the Pirate Nation.”

Mares’ guest post was the first time I noticed the term “food pyramid” connected to the Food Compass, though Mares does put the term in quotes, at least in the headline. He doesn’t explicitly say it’s the government’s advice, but he notes that the Food Compass study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and expresses concern that it could inform federal policies such as what’s served in schools. (The Tufts Food Compass paper notes the research was supported by Danone, a major food company, and grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at NIH, but says “the funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis or interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.”)

The Pirate Wires piece got some pick up. Mares told me he heard from a couple members of Congress after he wrote the post, though he declined to name them. Two weeks ago, that same post was revived in a Twitter thread by Calley Means, also co-founder of TrueMed. (I recently wrote about all of this here.) At this point, Mares and Means were both getting asked to speak on Fox News about different, but also sort of related, controversies: the Food Compass and Coca-Cola’s tactics to combat soda taxes. They each appeared in separate Fox News segments, but it was the Food Compass critique that caught fire at Fox.

“Primetime has broken open the biggest scandal since Watergate, bigger than Benghazi, bigger than Obamagate, even,” said Fox host Jesse Waters, in one of the openings (this particular segment featured Teicholz). As I wrote last week, these programs made numerous false claims, the biggest being that we have a new food pyramid and the repeated insinuations that the government has endorsed this research, something that, frankly, undermines other valid points of criticism that were raised, like rampant conflicts of interest in nutrition science and the health care system profiting from diet-related diseases.

Inviting threats: Fox News Primetime ran several segments slamming the government’s new “food pyramid,” without doing basic fact checks, and went as far as posting Mozaffarian’s email and phone number on air – predictably resulting in an onslaught of threatening messages aimed at Mozaffarian.

Mares told me he disapproved of how Fox handled the segments, particularly the posting of Mozaffarian’s personal information, but he stood by his criticism of the Food Compass: “This is so obviously a dumb glitch in the Matrix, that people can go: ‘food policy is messed up, here’s an example.’ I think that’s why it’s resonating with people.”

A valid methodology debate: As I wrote last week, I got in touch with Mozaffarian after this all initially blew up, and he readily acknowledged that the Food Compass has limitations, as all nutrient profiling systems do. In other words, the question of why, say, Frosted Mini Wheats score better than foods like a chicken breast or egg is a legitimate one.

“I accept constructive criticism, [like] ‘Whole grain packaged foods, that are mostly whole grain but are still packaged and processed and have some added sugar, should those be scoring as highly as they do?’… I think it’s a valid point,” Mozaffarian said. “We’re looking at ways to see if we can scientifically improve the scoring. We do account for processing, but maybe we should account for it even more.”

He also noted that the system scores hundreds of highly processed, refined grain cereals, breads, crackers, energy bars and other similar products lower than most animal products, including most fish, poultry, eggs, cheese and red meat.

“This is a major advance, has been missed by some of the critics who’ve looked for the exceptions, and is a significant improvement over existing systems used worldwide,” he said.

“One of the most dismaying things is that exaggerated controversy can be weaponized by the food industry,” Mozaffarian added. “If it seems everyone disagrees, then industry can claim that no one really knows anything about healthy eating. Rather than finding the many areas of common ground, some are emphasizing the few differences.”

Processing is a touchy subject: Ironically the Food Compass is probably one of the least-favorable nutrient profiling systems to most processed foods (other systems don’t account for any level of processing), which in theory might please the growing voices in the nutrition world arguing that ultra-processed food is driving diet-related diseases like obesity and diabetes. I’ve certainly heard that significant swaths of the food industry dislike the Food Compass for this very reason.

I asked Mares what he thought of this: What if the Food Compass is actually the rating system he would agree with the most?

“I think in the best case you could say this is slightly better,” he said. “But my read of it is that this was an absolute waste of money…It may be slightly in a better direction, but overall it just discredits the entire idea of what’s healthy and it ends up sending more people away from government nutrition and research and into the hands of influencers who say you should drink 50 gallons of lemon juice every day or eat only meat.”

Mares added, “The rise of this diet tribe stuff is, I think, a direct result of the fact that people fundamentally do not trust nutrition research and nutrition science.”

Chart zero: When unpacking this saga, I also talked to Beal, whose original chart took on a life of its own on the internet. Beal was pretty shocked by how it had all gone down. “I did not intend to have this go viral and I don’t agree with how it’s been used. It’s been taken out of context,” Beal told me. “I don’t think the Food Compass is terrible. There are some good things about it. It would improve upon the current U.S. diet, but – and we say this in our paper – there are legitimate concerns.”

Beal posted a lengthy Twitter thread this week to correct some of the claims that had spun out of control on the internet and add context to his original chart, though he stood by his overall critique. Beal pointed people to a soon-to-publish paper, where he and other scientists express some concerns about the Food Compass.

“While a conceptually impressive effort, we propose that the chosen algorithm is not well justified and produces results that fail to discriminate for common shortfall nutrients, exaggerate the risks associated with animal source foods, and underestimate the risks associated with ultra processed foods,” they wrote. “We caution against the use of Food Compass in its current form to inform consumer choices, policies, programs, industry reformulations, and investment decisions.”

Why this whole debate ultimately matters: Nutrient profiling systems are a bit technical and boring – setting aside this one time one went viral with a strong assist from misinformation – but we are likely to hear more about them as the FDA looks to develop a front-of-pack labeling system to help consumers identify and choose healthier foods. Though it’s a very long way from rubber meeting the road, it’s something I’m tracking closely.

I’ve yet to come across a food rating system that everyone thinks is not-problematic. (If you know of one, get in touch!) Any set of criteria can be gamed by food marketers or will favorably rate foods that many would consider less healthy options.

“No algorithm is perfect enough to kick out the foods you think it should kick out,” one industry expert told me. “It’s like pornography. You know it when you see it, but making an algorithm that adequately addresses it is the challenge.”

They added, “It’s going to get worse with FDA looking at front-of-pack. It’s going to get louder and more confusing.”

***

Wide range of experts named to the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Agriculture Department on Thursday jointly announced the lineup for the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, a panel of twenty experts who play an important role in helping the government update federal nutrition advice.

“The recent White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition and Health underscored the need to understand the science of nutrition and the role that social structures play when it comes to people eating healthy food,” said HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra.

Diverse group: The panel includes a notably broad range of expertise. For example, Steven Abrams of the University of Texas at Austin, a physician specializing in infant nutrition; Fatima Cody Stanford, an obesity medicine specialist at Harvard University; Angela Odoms-Young, a leading researcher on nutrition, food justice and health equity; Edward Giovannucci, an expert on cancer risk factors (also at Harvard); and Hollie Raynor, an expert on lifestyle interventions at the University of Tennessee.

Early reaction: Those who most closely track the guidelines process were still digesting the lineup Thursday – I didn’t get much initial reaction – but Jerry Mande, CEO of Nourish Science, praised the committee selections.

“It’s an outstanding committee including some of the nation’s top ultra processed food scientists,” Mande told me. “[Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack] did well to get ultra processed foods on the agenda.” (Ultra-processed foods is one of the topics the committee has been asked to look at.)

Thoughts on the panel? Send me a note. As a reminder, the first committee meeting will be Feb. 9-10.

***

What I’m reading

USDA moves to crack down on ‘organic’ fraud (Washington Post). This piece by Laura Reiley unpacks a new rule out of USDA this week aimed at strengthening the integrity of organic standards. Tom Chapman, CEO of the Organic Trade Association, told the Post that the updates represent, “the single largest revision to the organic standards since they were published in 1990,” adding that the rule “raises the bar to prevent bad actors at any point in the supply chain.”

Iowa bill would ban SNAP recipients from buying meat (DTN). This headline from Chris Clayton got an immediate click from me. Sometimes you hear conservatives wanting to make the food stamp program more like WIC, which limits the foods young families can buy, with the goal of weeding out soda and other sugary foods, but this story about legislation in Iowa notes that such a move would include axing meat. Clayton reports: “The bill, House File 3, has 39 co-sponsors in the Iowa House and is led by House Speaker Pat Grassley, a Republican. Pat Grassley is the grandson of Iowa U.S. Sen. Chuck Grassley, the longest-serving member of the Senate Agriculture Committee — the committee that writes the farm bill, including SNAP rules, in Congress.”

Fake meat was supposed to save the world. It became just another fad. (Bloomberg) I actually have this magazine cover story from Deena Shanker open on my computer. I haven’t had time to read it yet, but I really want to. The subhed: “Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods wanted to upend the world’s $1 trillion meat industry. But plant-based meat is turning out to be a flop.”

***

Support Food Fix by becoming a paid subscriber

If you find this newsletter useful, consider supporting this work by becoming a paid subscriber.

Subscribing to Food Fix unlocks access to not one, but two (!) newsletters each week, packed with insights and analysis about what on earth is going on with food in Washington and beyond.

Check out subscription options, including discounted rates for students, groups, academia and government. You can also follow Food Fix on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Get on the list: If someone forwarded you this newsletter, you can sign up for the free edition here.

See you next week!