Happy Friday, and welcome to Food Fix! I’m back in your inboxes just for today. (For those of you who are new around here, I had a baby in May and have been taking some time off.) Today’s edition is a bit different than our usual fare – instead of diving into a current issue, we’re going back in time to devour some presidential food history.

I’ve been wanting to run this Q&A for a while and this week feels like a good time. The news cycle is particularly chaotic right now – even for me and I’m pretty disconnected from it all in Babyland – so I hope you enjoy reading something a little different today.

Exclusive insight: While I’m here, a friendly reminder that you are missing out if you’re not getting Food Fix in your inbox twice a week as a paid subscriber. We’ve recently featured a rad rotation of guest writers offering insights on everything from the coming legal battle over cell-cultivated meat to a childhood obesity reality check and a guide to the new players lobbying on food in Washington. Earlier this week, journalist Jesse Hirsch reported on the Biden administration’s delayed efforts to crack down on salmonella in poultry.

Paid subscribers make Food Fix possible every week. Thank you for your support!

Alright, let’s get to it –

Helena

***

Inside the wild world of presidential food history

You might be familiar with journalist and author Alex Prud’homme for his previous books, on topics ranging from terrorism to water policy and kitchen design – though he’s perhaps best known for co-authoring his great-aunt Julia Child’s memoir, “My Life in France.” Last month, he was featured in a new Masterclass on food with José Andrés and former White House pastry chef Bill Yosses.

I first learned about Prud’homme by reading a review of his book “Dinner with the President: Food, Politics, and a History of Breaking Bread at the White House.” I’m pretty sure I purchased myself a copy before I’d even finished reading the review. As I told Prud’homme when we spoke a while back, I felt like this book was written for me – I almost wish that I had written it – but in any case, I so enjoyed reading it. You may remember I actually recommended this book to you all back in February – it’s a fantastic read for history lovers and food-policy nerds alike. It was a treat talking to Prud’homme about his book and the history lessons we can learn as told through the lens of food.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Helena: I love the quote at the very beginning of the book from the late Anthony Bourdain: “Nothing is more political than food. Nothing.”

I tend to agree with Bourdain. People have a tendency to think about food and even food policy as somehow frivolous or even cute, but it’s deeply political. I can tell you share that view. How did you come to that realization?

Prud’homme: I kind of feel like I was destined to write this book. I grew up in this very foodie family, not only with Julia Child who was my great aunt, everybody else was really into food, too, so I was completely spoiled. Amongst my family members were some civil servants in Washington and some diplomats abroad, including Julia and her husband, Paul. We would sit around the dining table talking about history and politics and food as we ate and drank.

Twenty years ago, when I was working with Julia on her memoir, “My Life in France,” I discovered that she spent quite a bit of time at the White House and had in fact made two documentaries about state dinners, one in ‘67 with Lyndon B. Johnson and the next in ‘76 when Gerald Ford hosted Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip for the Bicentennial. I got obsessed with state dinners and why they’re important. Like most Americans, I had heard of them, but I didn’t really know what they were. So that was one entry point for me.

There’s always an economic and diplomatic agenda to these things; they don’t just happen by accident. They’re highly coveted and important, and there’s a lot of groundwork that goes in beforehand. The dinner is really the conclusion of diplomatic and economic negotiations.

Food is an umbrella term that you can put almost anything under. It is arguably the biggest business in America. It has this enormous lobbying effort behind it. And it touches on everything from your personal diet and health, to local politics, global affairs, gender, race, religion and war.

Yes, it’s one reason I’ve never gotten bored of this beat. It’s both narrow and not narrow at all.

Yes! The more I researched what you might call the “hard news” about food, the more I became convinced that Bourdain was correct. There is nothing more political than food because it touches on everything. One of the things that drove this home was that I was not able to get a hold of any of the presidents or first ladies – they would not talk to me. I know they got my messages … but they would not respond. I realized that part of the reason is that food choices can be very revealing and intimate. And that makes people a little bit nervous. The other thing is that food is highly political and even after they’ve retired from politics, they still don’t want to touch it because it’s a third rail. I just thought that was fascinating.

Towards the end of the book, you argue that the presidents’ approaches to food weren’t really that different, Republican versus Democrat.

It wasn’t partisan. Basically, a lot of presidents like steak.

Yes, and they all liked ice cream except for Bill Clinton, who was allergic to it. I had no idea.

That’s kind of my experience, too. Food is often used as a political signal, but it’s also more universal than people realize, especially when you look at what they’re actually eating.

That’s the takeaway. It’s universal. We all need to eat, right? And historically, the dining table is a neutral space where you put your weapons aside and have a frank conversation outside of the normal political channels, away from the media. You broker business deals and diplomatic ties, and you have a laugh, right? It’s a way for leaders to get to know each other as human beings rather than as these cardboard cutouts. It’s hugely important.

The other thing is that human beings are biologically programmed this way. Not only do we like to eat together, but we need to eat together. When we eat in groups, it releases endorphins, which are the naturally occurring opioids in our bodies that make us feel good and reinforce that behavior, which has ensured our survival. We’re not fighting over resources; we’re clustering in groups that will protect us from predators. And it is arguably one of the reasons that civilizations were built: We’ve learned to harvest and hunt together and eat together. You’re more powerful as a team than you are as an individual. I just thought those deeper layers were worth including.

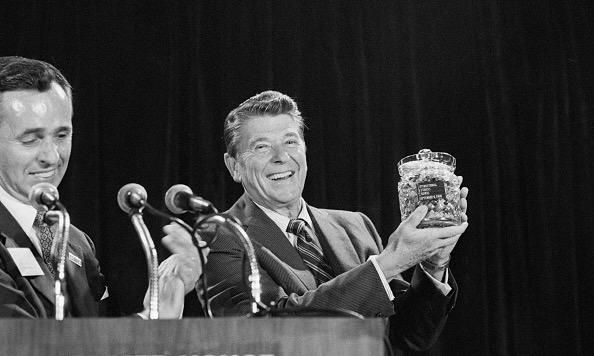

And then if you take that to the political level, there is a lot of messaging that goes on. Ronald Reagan and his jelly beans, for example.

I didn’t realize that it wasn’t just that Reagan liked Jelly Bellies. He helped make Jelly Belly a very successful American product. I loved the detail that 40 million red, white and blue jelly beans were consumed at his inauguration celebration.

The reason he got into Jelly Belly was that he was weaning himself from tobacco. And it was at [Nancy Reagan’s] insistence. So he’s replacing the nicotine high with the sugar high, and he was very friendly towards the sugar lobby. But then the sweets turned a little bit sour when he declared that ketchup – a great sugary substance – is a vegetable and defunded school lunches by almost $1.5 billion. It just so happened that the school lunch cuts were announced on the same day Nancy Reagan had ordered a beautiful, but expensive new set of White House china. So the message went from, ‘I like Jelly Belly and you like Jelly Belly so you should vote for me,’ to ‘the Reagans are really out of touch with the American public.’ People on all sides of the political spectrum reacted negatively to defunding school lunches.

I say several times in the book that when you’re the president, every bite counts – or every word about food counts – because you are living under a spotlight. When George H. W. Bush made a “joke” about broccoli, it backfired because the broccoli farmers understood that it could cost them millions of dollars and people would stop eating broccoli and so they trucked 10 tons of broccoli to the White House in protest.

It’s interesting to think that, since then, you can’t really think of presidents completely throwing one product under the bus, and I wonder if they all learned from that incident.

What’s interesting is that it’s a truism that the public pays attention to what the president and first lady eat. When we see somebody wearing a shirt we like, we think, “oh yeah, nice shirt,” but we don’t really think more than that. But when we see somebody eating something that we like to eat, it gets into our primal brain and it says to us, “I like this food. He likes this food, therefore I’ll vote for him.” That was part of the Jelly Belly thing with Reagan.

But Donald Trump used that with his McDonald’s burgers when he held his so-called burger banquet in the State Dining Room. He didn’t even have to say the words. The image was everything. And it was genius politically, think what you will of the guy. It said, “I like this food.” And it said to his voter block, “you like this food, vote for me.” And a lot of people did. That was sort of the reverse of throwing something under the bus: He exalted in junk food … I just thought it was fascinating – the psychology of food.

I was fascinated by how far back this went. If you had asked me before I read this book, I would have assumed that using food as a political campaign tool was more of a modern phenomenon: We see presidents eating on the campaign trail, or we see images of them hosting state dinners on TV. But you write that Abraham Lincoln often told a story about sharing gingerbread with an impoverished neighbor during the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates – it was seen as a way to appeal to the common man. Is this a theme you found across all presidents?

We’re at a moment in history where food is part of the national and international conversation in a way it really hasn’t been before. This general interest in nutrition and food has become part of the daily dialogue. At the Iowa State Fair, every journalist under the sun will go and look at the deep-fried butter sticks and the weird doughnuts you can get. Because of the shifting demographics, you can get bánh mì sandwiches and boba tea and Mexican specialties at the Iowa Fair, too. It’s just reflective of the changing nation.

Do you have a favorite anecdote from the book? I dog-eared so many pages to ask you about.

I opened the book with this so-called “dinner table bargain” hosted by Thomas Jefferson for Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, in which Jefferson uses food to seduce these enemies who are at each other’s throats and can barely look at each other, let alone speak to each other. Jefferson is worried that their fight is going to destroy the young republic. His enslaved chef James Hemings, the brother of Sally Hemings, cooks this fantastic meal. It’s just the three of them at a secret dinner, and they broker a truce with the help of a lot of good French wine and brandy. It is a dinner around which the fate of the nation hangs and it’s just amazing to me. I would have loved to have been a fly on the wall for that. That dinner is the basis for the song, “The Room Where It Happens,” in the musical “Hamilton.” So that has some contemporary resonance.

I don’t think people understand the extent to which food is right in the middle of all of these major events. When you look at the presidency and American history through this very particular lens, it opens up doors and interpretations. It gets you behind the scenes and into people’s heads.

There was a headline in The New York Times in 1939: “King tries hot dog and asks for more; and he drinks beer with them,” about Franklin Delano Roosevelt hosting King George VI and Queen Elizabeth to a quintessentially American picnic at Hyde Park in New York. It’s such a clear example of food diplomacy. It signaled that the Americans and the Brits were tight at a crucial point ahead of World War II. It was so much more than a hot dog and beer.

It was such a great theatrical moment. He totally stage-managed and it just shows you how smart he is – and how he understood, like Jefferson, but unlike many presidents, how to use food.

Another great moment was Richard Nixon, who survived on a little ball of cottage cheese on a pineapple ring for lunch almost every day – so sad and pathetic and sort of telling. But then he goes to China in 1972, and he’s eating this exotic shark fin soup and thousand-year eggs. And it succeeds beyond his wildest dreams: It makes him look presidential so he wins reelection in ‘72. He opens up the Chinese market to the West; he boxes the Soviets out of the geopolitical game.

And in the law of unintended consequences, he also sets up a whole new Chinese food craze here in America because people saw that he wasn’t eating just the glop that we were used to, but really sophisticated fare from all different regions of China. That’s another great moment – arguably one of the most important dinners of the 20th century.

Nancy Reagan was highly aware of the political significance of food and entertaining, and Jackie Kennedy was probably the master of that. One of the things I tried to do [in the book] is heighten the role of the first lady behind the scenes. It’s such an interesting phenomenon. They’re not elected, they’re not paid, and yet they play a really important role.

Maybe we can end on Dwight Eisenhower. You declared him the best presidential cook. How should we think about the president cooking versus eating? There seems to be a difference there.

Well, most presidents don’t cook. And a lot of the first ladies don’t cook either. But some of them do – some of the first ladies were wonderful cooks. You have to take it on a case-by-case basis. Eisenhower just loved to cook. He grew up on a farm in Abilene, Kansas. His mother taught him and his brothers how to cook. She was a pacifist, and he became a five-star general. She insisted that he learn how to cook and he married Mamie Eisenhower, who did not like to cook, so he cooked for his family.

When he was in the army, [Einsenhower] lived by Napoleon’s credo that an army runs on its stomach. He made sure that his troops were well-fed, not only in terms of quantity, but also in terms of quality. At a moment like the D-Day invasion, that mindset gave the United States a big advantage over the German troops, who were not particularly well-fed. When he was the president of Columbia University, he made headlines because he provided a school cookbook with his mother’s recipe for two-day vegetable soup, which is a fabulous creation, and one that I’ve made. It makes the whole house smell like beef broth.

As president, he would grill steaks and flip pancakes and talk about his recipes all the time. He was known as the president who cooks. But he also used dinners as a way of gathering intelligence from across the country. He would have these “stag dinners” in which he would invite business and other leaders to the White House, 15 men at a time. He would insist that everybody talk at the table and he would pepper them with questions. He would get the kind of information he could not get in Washington inside the Beltway. It was a very smart move that showed how to use food as a political tool.

If you’re interested in presidential food history, get yourself a copy of “Dinner with the President: Food, Politics, and a History of Breaking Bread at the White House.”

***

What I’m reading

Top Ag Republican offers bleak prognosis for farm bill (E&E News). “Congress might be better off leaving an already overdue five-year farm bill unfinished in 2024, Arkansas Republican Sen. John Boozman said Tuesday,” Marc Heller reports. “At a forum sponsored by POLITICO at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, Boozman – the top Republican on the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Committee – said extending the 2018 farm bill for the second year in a row would be preferable to passing a bill without significant changes in policy.”

USDA maintains bird flu can be eliminated from dairy cows, even as doubts mount among experts (STAT). “Facing increasing doubts that the U.S. can control the outbreak of avian influenza among dairy cattle, federal officials reiterated on Tuesday that they believe the country can still eliminate the H5N1 virus from dairy cows, even as it continues to spread to new herds,” writes Andrew Joseph. Some experts are skeptical, arguing that “the problems that have impeded the outbreak response from the beginning – from a surveillance system that isn’t keeping up with the spread of the virus to a lack of cooperation from dairy farms – haven’t changed dramatically. And they argue that the longer the virus persists in cattle, the more likely it is that it could mutate in such a way that would make it more transmissible among people.”

Inside Bobbie’s growth strategy as it launches on Amazon & opens a new factory (Modern Retail). “Organic infant formula company Bobbie is experimenting with selling its supplement products on Amazon this summer, part of a growth strategy that dovetails with a new domestic supply chain operation,” Melissa Daniels writes.” While Bobbie has recently faced supply issues, it is “poised to meet growing demand, as its new manufacturing plant in Heath, Ohio, is online as of this week.”

Kraft Heinz names former Pepsi marketer Todd Kaplan as North America CMO (Food Dive). “Kraft Heinz has appointed Todd Kaplan as CMO of its North America business, effective Aug. 5. Kaplan will spearhead marketing for a sprawling $22 billion packaged foods portfolio that includes the namesake Kraft and Heinz brands, along with dozens of other products like Oscar Mayer, Velveeta, Philadelphia Cream Cheese, Ore-Ida and Jell-O,” reports Peter Adams. “The executive jumps to Kraft Heinz from PepsiCo, where he spent nearly two decades and most recently served as CMO for the flagship Pepsi brand.”

***

Upgrade today to get more from Food Fix

Become a paid subscriber to unlock access to two newsletters each week, packed with insight, analysis and exclusive reporting on what’s happening in food, in Washington and beyond. You’ll also get full access to the Food Fix archive – a great way to get smart on all things food policy.

Expense it: Hey, it’s worth asking! Most paid subscribers expense their subscriptions through work. We also offer discounts for government, academia and students. See our subscription options. Individuals who participate in SNAP or other federal nutrition programs qualify for a free Food Fix subscription – just email info@foodfix.co.

Get the Friday newsletter: If someone forwarded you this email, sign yourself up for the free Friday edition of Food Fix. You can also follow Food Fix on X and LinkedIn.

The regular author of Food Fix, Helena Bottemiller Evich, is out on maternity leave. (Well, except for this issue.) Food Fix will feature a series of guest writers through July. Send feedback and story ideas to editorial assistant Lauren Ng at lauren@foodfix.co.

See you next week!

Correction: This newsletter originally incorrectly stated how much broccoli was sent to the White House to protest comments from President H. W. Bush. It was 10 tons.